In

AD 286, Maximian, newly appointed as co-emperor by Diocletian, was in Gaul

(modern day France) suppressing a revolt by runaway slaves and peasants known

as the Bacaudae. At this time the south-eastern coast of Britain and northern

Gaul were being subjected to raids by Saxon pirates and it was thought

necessary to create a naval force to deal with them.

Command

of this fleet was given to one of Maximian's lieutenants called Carausius, who

had already demonstrated his skill and valour. Soon after his appointment,

however, complaints were made that instead of returning any recaptured booty,

Carausius was expropriating it for his own use. Maximian ordered his arrest and

execution but Carausius forestalled this by sailing off to Britain and

declaring himself emperor. How this was accomplished is unknown and the

literary evidence for the chronology and events of this rebellion are extremely

scanty. The main sources are two panegyrics, one in honour of Maximian,

delivered by Claudius Mamertinus in AD 289, and the other by Eumenius in AD 297

for Constantius I. There are also sketchy accounts by Aurelius Victor and

Eutropius over half a century later, the ramblings of Geoffrey of Monmouth

written circa AD 1136, reputedly based on Welsh folklore, and the medieval

Scottish Chronicles of John of Fordun and Hector Boethius. Although writing a

thousand years after the event, the Chroniclers add many details not found

elsewhere, such as a supposed alliance with the Picts and Scots that enabled

Carausius to defeat the Roman garrison and take control of the island. In general these Chroniclers are in

agreement, that Carausius first sailed round Britain and then, after landing in

the north, defeated the Roman governor, Quintus Bassianus, in a battle fought

near York, though we cannot be sure of the truth of what may be total

fabrications.

So

little is known about Carausius that were it not for the famous Carlisle

milestone we would not even be aware of his full name. This stone, discovered

in 1875, bears the legend IMP C M AVR MAVS CARAVSIO INVICTO AVG. It had been

reversed in the ground and re-used in the time of Constantius I. His name and

titles were therefore Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Mausaeus Carausius the

Invincible (unconquered) Augustus (emperor). According to the historians he was

a citizen of Menapia, part of modern Belgium, and stress that he was "vilissime

natus" - of the most humble birth.

In

addition to Britain, Carausius must have controlled part of northern France,

because it was necessary for Constantius I, who was made Caesar of the Western

provinces on 1 March AD 293 and given the immediate task of recovering Britain,

first to capture the port of Gesoriacum (Boulogne). This he accomplished by

building a mole across the entrance to the harbour and preventing supplies and

reinforcements from being sent by Carausius. It may have been in a wave of panic

that followed the loss of Gesoriacum that the enemies of Carausius assassinated

him and made his chief minister, Allectus, emperor in his place (Aurelius

Victor says that Carausius was killed through the treachery of Allectus).

Meanwhile

Constantius secured the rest of Gaul and made his preparations for an

invasion. The prime obstacle facing him

was the "Classis Britannia", the British Fleet, already, it seems,

enjoying a fearsome reputation for its defeat of a previous invasion attempt by

Maximian in AD 289 (explained away by Roman historians as the result of an "inclementia

maris" - an inclement sea). Robbed of its main base at Gesoriacum it

now fell back on Clausentum (Bitterne in Southampton Water). In addition to the

fleet there was a series of forts guarding all the navigable estuaries around

the coast from Portchester, near Portsmouth in Hampshire, to the Wash, known in

later documents as the "Litus Saxonicum", the Saxon Shore.

Some of these forts were built in places with a long history, for example

Richborough in Kent, while others were completely new sites, such as Pevensey

in Sussex. All date from the latter part of the 3rd century and may either have

been built by Carausius himself or were part of the general defensive trend

inaugurated in the time of Aurelian (AD 270-275), who had ordered walls to be

built around Rome.

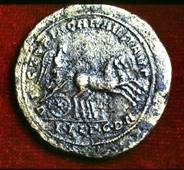

Unique bronze medallion of Carausius, datable

to circa AD 289

commemorating a victory, presumably the one over Maximian's fleet

Reverse:

VICTORIA CARAVSI AVG with I.N.P.C.D.A in exergue

Sold

in a London auction in the 1970s, this medallion is now in the British Museum

By AD 296

Constantius assembled two large fleets, one under his own command at

Gesoriacum, the other under his Praetorian Prefect, Asclepiodotus, at Rouen.

This latter force set sail first and on hearing this, Constantius hurried after

it. Thanks to a thick fog Aslcepiodotus managed to avoid the British Fleet and

landed near Southampton, burned his boats and marched for London. Allectus

gathered his army and advanced to meet them, but was

defeated and killed. The scattered remnant of his army fled back to London but

were prevented from sacking it by the belated but timely arrival of

Constantius.

This event was

celebrated by a large gold medallion showing Constantius entering the gates of

London and the legend

REDDITOR LVCIS AETERNAE (Restoration

of Eternal Light).

Constantius

I gold medallion showing him entering London

From

the Arras hoard, its weight is equivalent to 10 gold coins

Study

of the coinage of Carausius and Allectus has always been hampered by the

uncritical amassing of many coins which are contemporary forgeries (barbarous)

and the inclusion of misreadings, together with hybrids or inadequately

reported pieces. The extent of the barbarous copies should not be

underestimated; experience shows that a large proportion of the so-called coins

of Carausius fall into this category. As an example, of the 81 coins of

Carausius in the Penard Hoard, 58 were barbarous and some of the remainder

suspected of being so. When these are removed from consideration a much clearer

pattern emerges.

In

an article for the Journal of the British Archaeological Association 1959,

"The Mints and Coinage of Carausius and Allectus", and another that

was part of "Mints, Dies and Currency" published in 1971, R.A.G.

Carson, proposed that these coins, both the RSR series and others without

mintmark, were minted at Gesoriacum, pointing to the fact that their

distribution in British finds is almost entirely confined to the south-east of the

country and formed a higher proportion of the coins discovered in finds nearer

the coast. In his view, support for this theory came from the fact that this

coinage ceases by AD 293, around the time that Gesoriacum was lost to

Constantius. This view has since been challenged, not the least because the RSR

coins have now been found die-linked with coins from a mint in London.

Explanation of the RSR mark is not obvious and various suggestions have been

made in the past which gained some currency, including Rationalis Summae Rei

(Aurelius Victor refers to Allectus as "cum eius permissu summi rei"

) or Rationalis Summarum Rationum (the title of an officer in charge of

the mint). However, by far the most plausible and now widely accepted

explanation, is the one advanced by Guy de la Bedoyere, that it

actually derives from a quote in Virgil's Fourth Eclogue, "Redeunt

Saturna Regna" (The Saturnian Age returns - in other words a new

Golden Age). If this seems far-fetched, he also points out that the letters in

the exergue of the medal of Carausius shown above, I.N.P.C.D.A. are the initial

letters of the very next line, "Iam Nova Progenies Caelo Demittitur

Alto" (Now a new generation is let down from heaven above). Such

sentiments would be totally in keeping with the aims of Carausius expressed

elsewhere on the coins, for example ROMANO RENOV(at) ("Rome

Renewed").

Another mint,

almost certainly located in Gaul, issued aureliani of a distinctively

crude style, some of which are marked with the letter R (occasionally OPR) or

unmarked. These are assigned to Rotomagus, modern Rouen, on the basis of a

large hoard found there which consisted solely of these coins. Most of the

other coins of this mint have been found in northern France, though some made

their way to Britain. Gold aurei were also struck at this mint so it definitely

had official status. Furthermore, although Carson dated these coins to circa AD

291, hoard evidence has since shown that they are among the earliest issues of

the reign. A common reverse on the aureliani is TVTELA (Protection),

particularly apt under the circumstances. Although the workmanship on these

coins improves it never reaches the standards of the coins minted in Britain,

possibly because it did not remain in production for long.

Carausius

aurelianus - Rouen mint

Reverse:

TVTELA

This

still leaves open the attribution of the bulk of the unmarked aureliani,

which form some 35% of the coinage. That they are early in the reign is shown

by hoards terminating circa AD 289 in which they form a high proportion,

swelled, unfortunately, by the inclusion of many coins that were barbarous

forgeries. If this mint is not to be located in France then it must have been

located somewhere in Britain, produced prior to the signed coinage. The distribution

pattern in hoards offers no guidance to its location and Carson's evidence that

it was in the south-east does not stand up to close examination. There is a

suggestion that some of these coins have been die-linked to marked London

issues, but the context leaves the doubt that they may have been found among

barbarous coins (I have not found such links myself). If they were all minted

in Britain, a problem of attribution arises, dividing them between the two

known mints.

The

two main mints of Carausius and Allectus were undoubtedly situated in Britain.

The main one, responsible for about two-thirds of the marked coinage minted,

used the letter L in the mintmark and must surely be London. The other used the

letter C and was originally thought to be Camulodunum (modern Colchester) and

usually referred to as such. This attribution was challenged by Carson, who

thought that a better case could be made for Clausentum. His reason for this is

that among coins found in Colchester the proportion of London mint coins is

even higher than normal whereas something like parity would be expected. It is

also important to note that on some coins the mintmark is CL, which is not a

normal mint contraction of Camulodunum - we would expect to find CM or CAM. On

this basis, Clausentum does appear to have a better claim, but the case for

Colchester is not totally lost because a 2nd Century inscription shows that it

was called Colonia Victricensis and the Antonine Itinerary V lists it as

Colonia (as well as Camulodunum in Iter IX). These earlier names may still

apply in the later 3rd Century.

If so, this might well be contracted to CL.

Claims

have also been advanced in favour of Calleva (Silchester), one of the tribal

capitals. North of Southampton Water, a

distribution pattern for Calleva would be virtually the same as one based on

Clausentum, though it should be stressed that no such pattern has been observed.

Another suggestion worthy of consideration is that it was Glevum (Gloucester)

as in that period G and C were interchangeable. Unfortunately, as shown above,

the distribution pattern of C mint coins in hoards tends to be ambivalent and

supports no conclusion in particular.

Early Carausius aurelianus - C

mint

Reverse: COMES AVG

After

eliminating most of the extraneous material, it can be seen that the London

mint used seven different marks for Carausius, one shared with Allectus, who

added another three marks. At the “C” mint, there is a similar picture, eight

for Carausius, two for Allectus plus the one shared. The key to dating the

Carausian issues is the change from the early obverse legend IMP CARAVSIVS P F

AVG to IMP C CARAVSIVS P F AVG, which, from two unmarked aurei commemorating

Carausius' quinquennalia, can be dated to AD 290-291. The first of these

(RIC V, 3) with reverse legend PAX AVG VOT Vand would have issued after

completing his fourth regnal year and the second (RIC V, 4) with PAX AVG MVLT X

would have come after the completion of that year and looking forward to a

tenth year. From their style these two aurei were from the mint which signed

with RSR.

A number of coins bear the letters S P or S C in the field, with the exergue blank. They are found with both types of obverse legend, therefore span the changeover. At various times those with S P have been assigned to London, S C to the “C” mint, on the grounds of style. Carson eventually opted for them all being from the C mint but I have always found this difficult to support; for the moment they are listed in accordance with Carson’s arrangement. It may, however, be something much simpler, that all the S C are from the ”C” mint but the S P coins are from both. A detailed die-link study of this group might prove the point either way.

Silver

and Gold

The

mint thought to be at Rouen was the first to issue gold coins for Carausius.

The same somewhat crude portrait style and idiosyncratic legends found on

the bronze coinage are mirrored in the

aurei, for example, the continuation of the legend into the exergue on the

reverse of the example illustrated.

Aureus of Carausius,

Rouen mint.

Among

the early issues were a series of silver "denarii" , some

bearing the mintmark RSR. These silver coins, the first issued in the Roman

Empire for over two hundred years, included a unique reverse type showing

Britannia clasping hands with Carausius and bearing

the legend EXPECTATE VENI - "Come

thou long-awaited" - based on the line from the Aeneid, "Quibus Hector ab oris exspectate

venis". Since most of the gold coins from this reign are somewhat

later and extremely rare (Note 1), it is thought that silver was used in

this initial coinage because no other bullion was immediately available. It may

have been obtained by extracting the small amounts of silver from the billon

coins of earlier reigns, although other sources are possible since Britain is

known to have supplied silver refined from lead ores mined locally, for example

a large lead ingot discovered in the Roman fort at Richborough is marked EX ARG

(“without silver” i.e. silver extracted).

The

weights of the silver coins seem to vary considerably. Ignoring one specimen

said to weigh 5.96 gm, they range between 3 gm and 5.2 gm.

Included are some coins that may be contemporary forgeries, which does tend to

cloud the picture. Examination of the frequency table suggests that there were

two distinct standards, the first averaging circa 4.45 gm, followed by one

circa 3.4 gm. With only one exception all the observed coins weighing more

than 4 gm are marked RSR; of those below 4 gm half are marked RSR,

with an almost equal number without mintmark. The lower standard, equivalent to

1/96 libra, was similar to that adopted by Nero in the 1st Century AD.

Above: Silver "denarius" of Carausius with

RSR mintmark

Reverse:

FELICITAS, showing - a war galley with mast and rowers

If,

as appears to be the case, the RSR mintmark belongs to London, then there is a

definite sequence for the precious metal coins, of what appear to be heavy

silver "denarii" marked RSR, lighter "denarii" marked RSR

and then unmarked, then a gap of maybe two years before an issue of unmarked

aurei and finally the ML series.

Silver coins of

Carausius

More

than any other of the denominations under Carausius, the silver coins

proclaimed the hopes and aspirations of the regime, heralding a new golden age.

Those with the reverse RENOVAT ROMANO, showing a wolf with the twins Romulus

and Remus, were among the most prolific.

The EXPECTATE VENI reverse emphasised the message, but so did others

that were less obvious in their message, such as VBERITAS AVG. The galley reverse FELICITAS and those with

CONCORDIA MILITVM gave an assurance of the protection afforded by the Classis

Britannia and the army.

All

the signed London gold aurei of both

emperors, save for one of Allectus with mintmark MSL, have the common mark ML,

irrespective of issue. They conform to the late 3rd Century light aurei

standard of circa 4.6 gm (1/70 of a Roman pound) set by Carus and his sons (AD

282-285). Most of these gold coins of Carausius, except those from Rotomagus,

seem to be from fairly late in the reign, circa AD 290-292.

Gold coins of Carausius

and Maximian minted in London

Gold coins of Allectus

minted in London

|

SEQUENCE OF MINTMARKS Silver and Gold |

|||

|

Obverse:

IMP CARAVSIVS P F AVG (with

variations) |

Mintmark |

||

|

AD

286 - 287 |

Silver “denarius”

(heavy standard) |

RSR |

|

|

“

“ “ |

Silver “denarius”

(light standard) |

RSR |

none |

|

Obverse:

VIRTVS CARAVSI |

|||

|

AD

289 |

Gold aureus |

none |

|

|

Obverse:

IMP CARAVSIVS P F AVG |

|||

|

AD

290 |

Gold aureus |

none |

|

|

Obverse:

IMP C CARAVSIVS P F AVG |

|||

|

AD

291 |

Gold aureus |

none |

|

|

Obverse:

CARAVSIVS P F AVG or MAXIMIANVS P F AVG |

|||

|

AD

292 |

Gold aureus |

ML |

|

|

Obverse:

IMP C ALLECTVS PF AVG |

|||

|

AD

293 - 294 |

Gold aureus |

ML |

|

|

AD

294 - 295 |

Gold aureus |

MSL |

|

By

common consent, the earliest coins of Carausius were an unmarked series of

billon aureliani, with little or no silver, possibly made from melting

down coins of the late Gallic emperors. They were of crude style and poorly

made. However, the standard of his

coins improved rapidly and soon matched those of the main empire.

Aureliani of Carausius

Rev: LAETITIA

AVG Rev:VIRTVS AVG

no

mintmark no

mintmark

Rev: PAX AVG

Rev:

PAX AVG

London

mint “”C”

mint

Rev: PAX AVG - mintmark S

P Rev:

PAX AVG - mintmark S C

Note

similarity of style to London mint coin

above Note

similarity of style to unmarked coins above

|

SEQUENCE OF MINTMARKS |

||||||

|

Obverse: IMP C M CARAVSIVS AVG |

||||||

|

AD

286 – 287 |

Unmarked |

|||||

|

Obverse: IMP

CARAVSIVS P F AVG |

||||||

|

Date |

London |

“C” mint |

|

|||

|

AD

287-290 |

ML |

C |

C | |

| C |

||

|

L | |

MC |

SMC |

||||

|

F | O |

MCXXI |

CXXI |

||||

|

B | E |

S | C |

S | C |

S | P |

|||

|

Obverse: IMP C CARAVSIVS

P F AVG |

||||||

|

AD

291 |

B | E |

S | C |

S | P |

|||

|

AD

292 |

S | P |

S | C |

||||

|

Obverse: IMP DIOCLETIANVS P F

AVG IMP C MAXIMIANVS P F

AVG CARAVSIVS

ET FRATRES SVI (“C” mint) |

||||||

|

AD

292-293 |

S | P |

S | P |

SPC |

|||

|

Obverse: IMP C

CARAVSIVS P F AVG |

||||||

|

AD

293 |

S | P |

S | P |

||||

|

Obverse: IMP C

ALLECTVS P F AVG |

||||||

|

AD

293-295 |

S | P |

S | P |

||||

|

S | A |

||||||

|

S | A |

S | P |

|||||

NOTES:

There are minor variations in obverse

legends not shown above

e.g. IMP CARAVSIVS P AVG. and sometimes A, AV or AG instead of AVG.

The dates shown are only intended to be approximate.

Although

Carson allocated a year to each mint mark, analysis of hoards show that some of the marks were are much rarer than others,

and were probably struck over a much shorter period. In particular the SMC mark

on Carausian aureliani was of brief

duration and probably contemporary with the previous mark MC. Nor did each mint

change its marks in synchronisation with the other.

One

mark attributed to London, that with just XI in the exergue, is almost

certainly barbarous, mistakenly copied from ML. However, the letters XXI added to the

mintmarks circa AD 290-292 served the same purpose as those found on billon aureliani

from Aurelian's reform in AD 274 onwards, intended as a value mark indicating

the silver content.

All

the London mint gold aurei of both

emperors, save for one of Allectus with mintmark MSL, have the common mark ML,

irrespective of issue. They conform to the late 3rd Century light aurei

standard of circa 4.5 gm (1/70th of a Roman pound) set by Carus and his sons

(AD 282-285). Most of these gold coins of Carausius, except those from

Rotomagus, seem to be from fairly late in the reign, circa AD 290-292.

Carausius aurelianus - London mint

Reverse:

SOLI INVICT - Sol in a quadriga

A

feature of the early coins of Carausius was the adoption of reverse designs

that were based on coins from previous emperors. Among these were SOLI INVICTO

(quadriga) and ADVENTVS AVG (Emperor on horseback) based on coins of Probus,

GERMANICVS MAX V and VICTORIA GERM from Gallienus, MONETA AVG from Postumus and

HILARITAS AVG from Tetricus I. This, coupled with the sub-standard style and

execution of the coins, is what would be expected for a rebel without mint

facilities immediately to hand who had to set everything up from scratch.

Legionary Series

One

interesting series in the early coins, are those aureliani that listed

nine different legions, showing their regimental emblems. As with a previous

legionary series issued by Gallienus circa AD 258-259 which may have provided

the inspiration, these coins were extensively copied. "Roman Imperial

Coinage Vol. V Part ii" lists twenty-three different reverse legends and

types, each with up to four obverse variants and several different mintmarks,

most of which, where it was possible to examine them, turned out to be

contemporary forgeries.

Legionary coins of Carausius - London mint

Left:

LEG I MIN Right LEG II AVG

|

Mintmark: ML |

||

|

Name |

Badge |

Normal

Station |

|

LEGI I

MIN(ervia) Also: |

Ram |

Lower Rhine |

|

Mintmark: C |

||

|

Name |

Badge |

Normal

Station |

|

LEG IIII

FLAVIA |

Centaur (Note

3) |

See above |

These

legions appear to be the ones that provided vexillationes

(detachments) allocated to Carausius for his defence of the Channel. If, as

seems to be the case, they retained their allegiance to their commander in his

revolt against Rome, it helps explain why he was such a difficult opponent to

dislodge. At first sight there is an obvious omission, Legio VI Victrix, which

was normally stationed at Eboracum (York). This omission, coupled with the fact

that the legion was omitted by Gallienus in his Legionary coinage and also from

a series of gold coins issued by the Gallic Emperor Victorinus (AD 268-270),

has led to speculation that it had been transferred away from Britain,

especially when there is no direct proof that it was in Britain after the reign

of Severus Alexander (AD 222-235). Against this is the fact that the late 4th

century/early 5th Century Notitia Dignitatum still lists Legio VI

Victrix in York as part of the British garrison. The omission was almost certainly because its

primary duty was the protection of Hadrian's Wall and so was not to contribute

to any field force serving Gallienus,

Victorinus or Carausius.

It

was customary for legions to operate in pairs on active service. If there were

two legions in a province they would combine together in the field for operations,

or if there was only one, it would be combined with a legion from an adjacent

province. In the legions listed by Carausius these paired formations can be

detected, two from Britain, two from Upper Moesia, two from Lower Germany, and

two from Upper Germany, together with Legio II Parthica from Italy as the

headquarters battalion. Together with

auxiliaries and cavalry units, such a force might comprise 10,000 or more men.

![]()

Obverse

legends and bust types

Carausius aurelianus with armoured bust

Legend:

IMP CARAVSIVS A

Although

the coinage of Carausius and, to a lesser extent, Allectus, do contain wide

variations, after the initial coinage, the most common reverse type by far

throughout the reigns of Carausius and Allectus was PAX AVG, in fact for

Carausius any other reverse is fairly scarce. Most of the variations came in

the obverse design, with the use of portrait busts showing Carausius with a

spear and shield (though such coins are rare), and include some with helmeted

busts, including one aureus copied from an aureus of Postumus. Another obverse that probably derived from

another Postumus aureus is that with a bare-headed facing portrait bust.

An early

facing bust coin that is probably modelled on an aureus of Postumus

Note the absence of the

radiate crown that would signify an aurelianus

“C” mint

As

a fairly general rule, on the bulk of the coinage the obverses of Carausius are

usually draped and cuirassed , while Allectus favours cuirassed busts. There

was also various shortening of the obverse legend, for example using A or AV

instead of AVG, omission of the letters P F, and the addition of the title I,

IN or INV (Invictus) on coins after AD 289. Another variation, used on

early aureliani modelled on those of Probus, was the legend VIRTVS

CARAVSI (AVG), an obverse legend that was also used by his successor (VIRTVS

ALLECTI AVG).

Aureliani

of Allectus

(left) with cuirassed bust, London mint

(right) with draped and cuirassed bust and legend

including I(nvictus), C mint

Both

Carausius and Allectus used helmeted busts, always facing left. Those for Carausius are found only on his

early coins, all prior to his victory over Maximian in AD 289 and are

completely absent from coins with later mint marks. Helmeted busts of Allectus

are extremely rare and were only minted by London. The one illustrated set a record price for an

aurelianus of Allectus when sold in ?????.

Helmeted busts of

Carausius an Allectus, holding spear and shield.

“Carausius

and His Brothers”

CARAVSIVS

ET FRATRES SVI

showing Carausius, Diocletian and Maximian together

“C” mint

Reverse:

PAX AVG

During

the period when Carausius , for whatever reason, acknowledged Diocletian and

Maximian as fellow-emperors he issued a series of coins in their names, both

individually and on the celebrated obverse CARAVSIVS ET FRATRES SVI (Carausius

and his Brothers), which shows the jugate heads of all three. Strict observance

of protocol meant that Diocletian was in the centre, flanked by Maximian on his

left as the senior co-emperor and therefore Carausius on his right. Among the

coins for Maximian were aurei from the London with mintmark ML, which

helps in confirming the date of that particular group.. Iti is possible that

originally there were also aurei struck in the name of Diocletian but

none have survived. Reverse legends on both the gold and the silvered-bronze

radiates from this period terminate in AVGGG to denote the three Augusti.

Aurelianus of Carausius with

reverse legend PROVIDE AVGGG

From

the sequence of marks, Carson made the observation that these coins date from

circa AD 292 and not, as previously supposed, after Maximan's defeat at the

hands of the British Fleet in his ill-fated expedition. From this he deduced

that far from being evidence of tacit acceptance of Carausius by Diocletian and

Maximian, they were more likely to be a diplomatic overture by the British

emperor in the face of the hostile build-up of forces in Gaul though Aurelius

Victor, “De Caesaribus”, says the “Carausius was allowed to retain his authority

over the island after he had been judged quite competent to command and defend

its inhabitants against warlike tribes”. This is ambiguous in that it may be

why Carausius was left alone for a while but does not explain the events that

followed. Instead, I would like to turn Carson’s argument on its head. In my

opinion, it is possible that after the failed attempt at invading Britain

overtures were made by Diocletian and Maximian that were intended to lull

Carausius into thinking that he would be recognised as co-emperor, stringing

him along with false promises until they were ready to act. The adoption by Carausius of the additional

title of Caesar implicit in the longer obverse legend on coins from AD 291 onwards

may have been part of this deception. If

this is what happened, the stratagem worked.

Carausius believed so much he was prepared to include both emperors in

his coinage until after the appointment of Constantius and realised that he had

been duped. When it finally dawned on

Carausius that any hopes he may have had for an alliance were in vain, these

coins ceased and were replaced by a new issue in his name alone.

According

to Aurelius Victor, Allectus killed Carausius in order to escape execution for

unspecified misdeeds, presumably in his role in charge of finances. Although this maybe be truth, it is easy to

imagine that Carausius might have been murdered as retribution for placing his

trust in Diocletian and betraying his supporters. Perhaps he also failed to

listen to warnings that he was being set up until it was too late.

|

COINS OF CARAUSIUS ISSUED IN HIS OWN NAME, |

||||

|

Mintmark |

Reverse |

Carausius |

Diocletian |

Maximian |

|

Gold aurei |

||||

|

| |

CONSERVAT

AVGGG |

x |

|

|

|

Aureliani |

||||

|

S | P |

COMES AVGGG |

x |

|

|

|

S | P |

COMES AVGGG |

x |

|

|

|

SPC |

CONCORDIA

AVGGG |

x |

|

|

London

mint aureliani of Diocletian and Maximian

“C” mint aureliani of Diocletian

Consulships

The

Gallic emperors, Postumus, Victorinus and the Tetrici, assumed the normal

offices and titles of an emperor, proclaiming on their coins that they were

Pontifex Maximus, Tribunicias Potestas, Pater Patriae and Consul (usually

abbreviated to P M, TR P, P P and COS). These were only applicable to the

territory under their control, separate and in parallel with, those of the

central empire. Although Carausius and

Allectus appear to have done the same, on the evidence of their coinage the adoption

of these offices never seemed to have been of great importance.

There

is reference to a consulship by Carausius found on his early silver coins on

which he is shown wearing a consular robe and holding an eagle-tipped

sceptre. There are some extremely rare aureliani

from the “C” mint that are more specific, including one in the British Museum

that has a reverse PM TR P IIII, with the rest of the legend off-flan. The style and fabric of the coin is early, so

there must be some reservations about the TR P reading, which would date the

coin to AD 290. Another, also from the “C” mint, quoted by RIC V has P M [……..]

COS P P. If the consulship was as highly

regarded as elsewhere, it is odd that coins celebrating the event should be so

rare.

Silver

“denarius” of Carausius wearing a consular robe

Reverse:

VBERITAS AVG. Mintmark: RSR

A

similar situation arises with Allectus.

That he held a consulship can be inferred only from London mint aureliani

where his obverse bust is wearing a consular robe (RIV V, 33 and 35). Rather oddly, these bear both of his first

two London mintmarks, S/P//ML and S/A//ML.

The question remains: were Carausius and Allectus ever consuls? Could it be that in the case of Carausius,

the reverses were copied from coins of previous emperors? With Allectus, was it just the rendition of

the obverse bust that was copied from coins of previous emperors, or even

contemporary Lugdunum mint aureliani

of Diocletian? There was no shortage of prototypes on which to base such a portrait..

The so-called“Quinarii”

The

last series for Allectus were small coins retaining the radiate-crowned obverse

bust of the aurelianus but only three-quarters of the previous weight.

Because of the letter Q in the mintmark, this coin is often referred to as a "quinarius",

though Besley in his report on the Rogiet hoard preferred to use the term

“Q-radiates”. Although thought of as a

reduced-weight aurelianus, their reported silver content of about 1.6%

would support the view that they were half-aureliani and therefore had

a value of about 1/500 of an aureus. Besley suggests that they were

introduced at a standard that equated to the old antoninianus just prior to

Aurelian’s reform.

There

is a difficulty with this in that based on published figures and depending on

which set of figures are used, the intrinsic value of the Q-radiate, based on

silver content alone, is between a quarter and a fifth of the aurelianus

and not half. Assuming that the Allectus aureliani still adhered to the

XXI standard, their silver content as a percentage was more than double that of

the Q-radiates, which, coupled with the lower weight of the latter, equates to

something like 4.5 to one and even using the lowest standard quoted for the

aurelianus and the highest for the Q-radiate, the ratio would be about 3.75 to one.. It may be pure fantasy, but

might that be the explanation of the enigmatic Q marking? See Appendix 2 for details of the

calculations involved.

The

reverse type depicts a galley, but the two mints available to Allectus mostly

used different legends, VIRTVS AVG at London and the “C” mint, the other being

LAETITIA AVG, which was only used at the “C mint”. Besley thought that the LAETITIA reverse came

before VIRTVS, with the likelihood that production by London started later.

Although

the galley on the reverse was common to all of these Q-radiates, within

themselves there was considerable variation.

The galley may face either right or left, the number of oars varied,

London coins often include a representation of the waves beneath the ship, a

feature that occurs at the “C” mint but is much rarer. . Some have a shelter or cabin beneath the

curving stern post, the ram on the prow is more prominent on some than others,

the heads of the oarsmen can also be large or small and do not always match the

number of oars. On galleys facing left

the steering board at the stern is shown. A scarce variant found on coins from

both mints is where there is a bird standing on top of the mast. On a small

number the galley does not have a mast. The most unusual and very rare types,

however, are those that show a figure of Victory either standing on the prow or

at the stern. Even rarer on those where

the galley does not have mast, one has Victory standing in the centre and one

with a river god reclining on deck.

Allectus

"quinarius", “C”

mint Allectus

“quinarius”, London mint

LAETITIA

AVG (galley

right) VIRTVS

AVG (galley left

Left: galley with multiple oars “C” mint

Right; galley with waves beneath, London mint

|

“Quinarii” |

|||

|

“C”

mint only |

|||

|

Date |

Reverse |

Mintmark |

|

|

Obverse: |

|||

|

AD

294-296 |

LAETITIA AVG (galley

left) |

QC |

|

|

Obverse: IMP C ALLECTVS P F AVG IMP C ALLECTVS AVG IMP ALLECTVS P AVG |

|||

|

AD

294-296 |

LAETITIA AVG (galley

right) |

QC |

|

|

Date |

Reverse |

London |

“C” mint |

|

Obverse: IMP C ALLECTVS P F AVG |

|||

|

AD

294-296 |

VIRTVS AVG (galley

eft) |

QL |

QC |

|

AD

294-296 |

VIRTVS AVG (galley

right) |

||

|

“C” mint only |

|||

|

Obverse: IMP C ALLECTVS P F I

AVG IMP C ALLECTVS AVG |

|||

|

AD

294-296 |

VIRTVS AVG (galley

left) |

QC |

|

Appendix 1

Barbarous copies of coins of Carausius and

Allectus

Contemporary

forgeries of Roman coins (usually referred to as "barbarous") can

nearly always be associated with the introduction of a new coinage, when the

forgers took advantage of public unfamiliarity with the new types, or times of

upheaval and unrest. The coins of Carausius fell into this both these

categories and forgers were quick to exploit the opportunities afforded by his

initial aureliani, which were of a poor style and execution, as well as the

novelty of his silver coins. By contrast his later coinage, produced to a much

higher standard, is hardly ever copied. This is also true of the coinage of

Allectus and although barbarous coins are known they are consequently much

rarer. Illustrated below are examples of barbarous copies for both emperors.

Barbarous

copy of Carausius Barbarous copy of

Allectusus

Appendix 2

In a study I made the

average weight of the Allectus aureliani was 2.70g (1/120 libra)

Notes:

1. Or

maybe because subsequent to the restoration to Roman rule measures were taken

to remove all vestiges of the usurpation, hence, for example, the treatment of

the Carlisle milestone.

2. This

coin, which I have been unable to verify, is open to suspicion as a

contemporary forgery because it uses the wrong badge.

3. Reinforcing

the supposition that anything to do with the usurpation was suppressed, these aureliani

in the names of Maximian and Diocletian turn up in later hoards which exclude

all other coins of Carausius and Allectus.

References:

Illustrations:

Coins on a red background are in the British

Museum

The Arras medallion is taken from an electrotype presented to me by M. Bourgey

of Paris in 1972 as an appreciation of some cataloguing work I had undertaken

on his behalf.

It has been digitally enhanced and colourised

to give a better idea what the actual coin looks like.